Originally published on Unily.

One of the most challenging areas for any business is how to capture, keep hold of, and make use of knowledge to sustain and improve business performance. It has a somewhat mysterious and complex quality: it’s more than data, facts or information. Knowledge is the sum of experience, expertise and human intuition — knowing the best way to solve a problem, or how to do something the right way.

It can be the perspective of an individual, the collective wisdom of a group, or even built into a product. Knowledge is often overlooked as a key differentiator in comparison to the more physical company assets: who uses and nurtures it to the fullest extent can have a huge competitive advantage. Losing it can mean an organisation can quickly cease to function.

How you manage knowledge is tricky to get right and differs from one company to the next. Today paradoxically, with so many new technologies to play with, it’s even harder to master. To help unpick all of this, it was a pleasure to get time to speak to one of the best knowledge managers in the business, Janine Weightman, Knowledge Manager for Penspen.

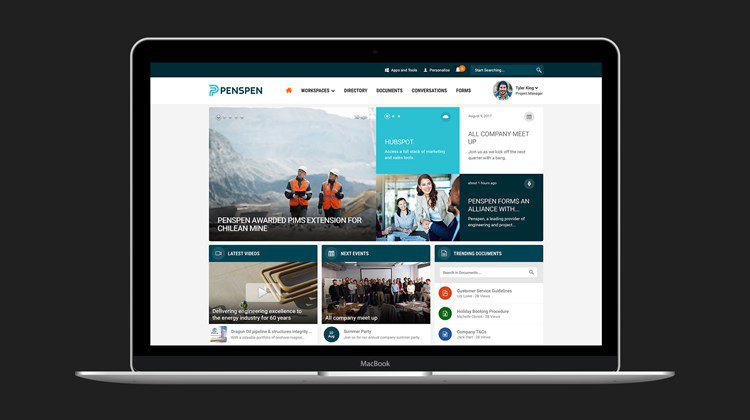

With headquarters in London and offices around the world, Penspen are an energy services company that provide customised engineering and project management services to the oil and gas industry to develop and rehabilitate energy assets across the entire project lifecycle. Weightman’s brief was to help Penspen embed knowledge management into the every-day life of every employee — be they engineers, project managers, or people on the road — working across the world, often in challenging and high-pressure environments.

‘It’s like asking someone to go on a long journey and expecting them to go on their push bike, rather than letting them have a car to make the journey easy.’

What makes Penspen very interesting is that they started out improving knowledge sharing capabilities before addressing their internal communication requirements. Normally it’s the other way round when organisations embark on redesigning their intranet or digital workplace.

Weightman’s starting point was to replace their existing SharePoint 2010 intranet that evidently wasn’t able to keep up with her knowledge management (KM) strategy. They wanted a new platform that could provide them with more options that complimented and enhanced the way their people work. ‘It’s like asking someone to go on a long journey and expecting them to go on their push bike, rather than letting them have a car to make the journey easy.’

Penspen chose Unily to support their vision, providing them with a solid central platform for knowledge management. As we shall see, it provided them with crucial functionality to support how their global workforce interact with one another.

Getting the right technology foundation in place became a key focus of her early objectives before anything else could happen. Following her assessment of Penspen’s KM requirements, Weightman discovered that there was an appetite for knowledge sharing but it was limited by the necessary infrastructure needed to sustain it effectively. As she told me ‘Could we survive with what we’ve got at this point in time? Of course we would be able to, but it’s making sure we’ve got that foundation where we don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time.’

Her aim was a place where staff could work with one another seamlessly, where they didn’t notice the technology at all. Her mission was about giving staff the right tools in the right context. As she went on to explain, they wanted an ‘integrated system where it’s a one-stop-shop where people can come together and do work.’

‘it should be so easy or not even noticeable that people are even ‘doing’ knowledge management.’

Continuing she said ‘it should be so easy or not even noticeable that people are even ‘doing’ knowledge management.’ This is a key point. If a business can introduce a better way of working — albeit tools, spaces to collaborate, the sharing of ideas — at the point of need, staff are more likely to value KM without being additionally burdened with something else to master.

With Unily in place, it meant every employee could have a targeted set of tools and content tailored to them, helping Weightman’s mission of getting the right knowledge in front of the right staff much easier to achieve.

Weightman continued to add more depth to the conversation, explaining to me that it’s not just a matter of getting the right tools in place. Rather, the more difficult challenge is ‘how do you weave [knowledge management] into an existing business process.’

For example, she explained that staff will ordinarily share knowledge between themselves, at a small scale, between their immediate teams but the question that needed to be answered was how could it be made to scale across larger teams or between other localities?

Her answer was that to make knowledge sharing happen on an organisation-wide scale involves building up trust between colleagues and confidence in the system. To the extent that they feel able to work out loud with one another without feeling self-conscious or out of their depth. As she explained, the goal was to foster trust ‘on an organisation scale, across cultures, across language barriers.’

Putting that into practice, as Weightman explained, meant having plenty of spaces in place too, where staff feel able to connect with one another. For example, communities of practice where people can share similar ideas with one another and have a sense of identity, regardless of where they are physically located. Unily provides the platform to make this possible.

Without these communities and connection points being in place, staff would remain both in silos and fragmented across the business with limited opportunity to draw on the collective value of the business and tools. Put simply, Weightman argued that ‘best way to share knowledge around a company is to make sure your people are connected.’

‘the harder task is to capture new ideas’

However, if those spaces are only used to access existing knowledge, then as she told me, the job of fostering organisational knowledge is only half done. Rather, the harder task is how to mobilise new ideas, knowledge, conversations that might only exist for example inside someone’s head, or deep within the collective wisdom of a group solving a current business problem.

For a business like Penspen who operate in a very changeable market, knowledge that has not been captured to the organisation’s ‘memory’ can be a very real risk. With people retiring, others coming on board with different skills, with evolving technology and engineering practices, the transfer of knowledge is a very real business critical issue. How successful companies are at doing this is indicative of their ‘intellectual health’.

Weightman explained the problem at Penspen. ‘Say for example if we put up an article or a post, from my perspective, it’s information. It’s not necessarily knowledge.’ But, as she went on, ‘it’s how that information prompts others to improve, or make use of it, that is key.’

She continued ‘…somebody reacting to that post, seeing it as an improvement opportunity or a lessoned learned or a best practice, or adding a comment on the post, which adds further insight or asks a question – that for me is the tactical business knowledge that you lose on a daily basis if you don’t have this infrastructure [in place].’

‘when social features are enabled into business processes, then I think you have won the battle.’

Where all this points to is the importance of social tools. What was useful to hear from Weightman was her emphasis on the real benefit of social tools: deeply integrating them into the fabric of how staff work.

Weightman went on to explain ‘…when social features are enabled into business processes, then I think you have won the battle… because then it becomes relevant. It’s part of work and people are doing it for a reason.’

To reiterate the point, she said it’s still the same ‘transaction’, but you’re doing it through a more ‘efficient and reusable means.’ For example, ‘instead of just sending that person an email, why not put your comment onto their post, or article, or even do a ‘shout out’ on a particular channel for that side of the business.’

‘there are no search fairies in the world, and content doesn’t miraculously fall into a search engine.’

What about search? After all, if you can’t find something, none of this can happen. Half-jokingly she replied saying if you expect to find things using one keyword, ‘there are no search fairies in the world, and content doesn’t miraculously fall into a search engine.’

Instead, to make search work, you’ve got to put the effort in to get it right: it’s a never-ending task because of the many new ways staff want to make use of their knowledge. Weightman told me that she appreciates ‘that it’s going to be a live, living breathing thing. As it evolves, we’re going to fine tune it to match it to people’s needs. And also… map the knowledge of the organisation.

‘help people discover what they don’t already know.’

What was refreshing to hear was that the onus should be on how the platform is designed not on expecting staff to put in additional effort to find something. Hence her simple rule is ‘instead of trying to find things, help people discover what they don’t already know.’

As a passionate knowledge manager, Weightman became animated telling me why these projects tend to fail: ‘People don’t have the time to go looking for things. It’s down-right cheeky for organisations to expect people to come and do their job and then go and find what they need in a rabbit warren of folders or search for the organisation’s crystal ball of knowledge!’

What this really points to is the need to invest in knowledge managers like Weightman. Without an ounce of arrogance, she said her role had become crucial because there needs to be someone responsible for ensuring that knowledge is being captured in the best way throughout the entire business.

‘I would say that is a fairly big indicator of a positive impact’

With my time nearly up, with everything achieved so far, has it been a success? Aside from its contribution in helping staff work more efficiently, she said another goal of KM should be to ‘bring about a change in behaviour’. The measure of success for a digital workplace designed to enable KM should be that it helps staff feel happier in what they do by enabling them ‘to just get on and do their job’.

To Weightman’s credit, the extent of what she has already managed to achieve has been recognised by management too. She told me they thought ‘it’s light-years ahead of where they expected us to be. I would say that is a fairly big indicator of a positive impact.’

Originally published by BrightStarr.